Developing AI literacy in your writing and research

Dr Lynette Pretorius

Contact details

Dr Lynette Pretorius is an award-winning educator and researcher specialising in doctoral education, academic identity, student wellbeing, AI literacy, research skills, and research methodologies.

I have recently developed and delivered a masterclass about how you can develop your AI literacy in your writing and research practice. This included a series of examples from my own experiences. I thought I’d provide a summary of this masterclass in a blog post so that everyone can benefit from my experiences.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been present in society for several years and refers to technologies which can perform tasks that used to require human intelligence. This includes, for example, computer grammar-checking software, autocomplete or autocorrect functions on our mobile phone keyboards, or navigation applications which can direct a person to a particular place. Recently, however, there has been a significant advancement in AI research with the development of generative AI technologies. Generative AI refers to technologies which can perform tasks that require creativity. In other words, these generative AI technologies use computer-based networks to create new content based on what they have previously learnt. These types of artistic creations have previously been thought to be the domain of only human intelligence and, consequently, the introduction of generative AI has been hailed as a “game-changer” for society.

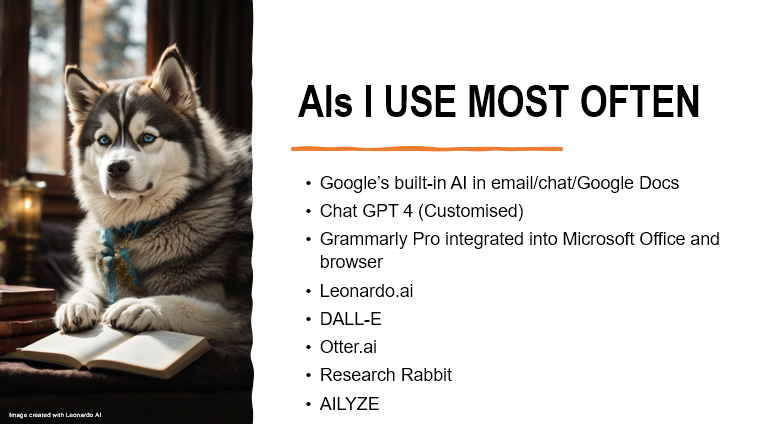

I am using generative AI in all sorts of ways. The AIs I use most frequently include Google’s built-in generative AI in email, chat, Google Docs etc. which learns from your writing to suggest likely responses. I also use Grammarly Pro to help me identify errors in my students’ writing, allowing me more time to give constructive feedback about their writing, rather than trying to find examples. This is super time-saving, particularly given how many student emails I get and the number of assignments and thesis chapters I read! I also frequently use a customised version of Chat GPT 4, which I trained to do things the way I would like them to be done. This includes responding in a specific tone and style, reporting information in specific ways, and doing qualitative data analysis. Finally, I use Leonardo AI and DALL-E to generate images, Otter AI to help me transcribe some of my research, Research Rabbit to help me locate useful literature on a topic, and AILYZE to help conduct initial thematic analysis of qualitative data.

The moral panic that was initiated at the start of 2023 with the advent of Chat GPT caused debates in higher education. Some people insisted that generative AI would encourage students to cheat, thereby posing a significant risk to academic integrity. Others, however, advocated that the use of generative AI could make education more accessible to those who are traditionally marginalised and help students in their learning. I came to believe that the ability to use generative AI would be a core skill in the future, but that AI literacy would be essential. This led me to publish a paper where I defined AI literacy as:

AI literacy is understanding “how to communicate effectively and collaboratively with generative AI technologies, as well as evaluate the trustworthiness of the results obtained”.

Pretorius, L. (2023). Fostering AI literacy: A teaching practice reflection. Journal of Academic Language & Learning, 17(1), T1-T8. https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/891/435435567

This prompted me to start to develop ways to teach AI literacy in my practices. I have collated some tips below.

- Firstly, you should learn to become a prompt wizard! One of the best tips I can give you is to provide your generative AI with context. You should tell your AI how you would like it to do something by giving it a role (e.g., “Act as an expert on inclusive education research and explain [insert your concept here]”). This will give you much more effective results.

- Secondly, as I have already alluded to above, you can train your AIs to work for you in specific ways! So be a bit brave and explore what you can do.

- Thirdly, when you ask it to make changes to something (e.g., to fix your grammar, improve your writing clarity/flow), ask it to also explain why it made the changes it did. In this way, you an use the collaborative discussion you are having with your AI as a learning process to improve your skills.

The most common prompts I use in my work are listed below. The Thesis Whisperer has also shared several common prompts, which you can find here.

- “Write this paragraph in less words.”

- “Can you summarise this text in a more conversational tone?”

- “What are five critical thinking questions about this text?”

I have previously talked about how you can use generative AI to help you design your research questions.

I have since also discovered that you can use generative AI as a data generation tool. For example, I have recently used DALL-E to create an artwork which represents my academic identity as a teacher and researcher. I have written a chapter about this process and how I used the conversation between myself and DALL-E as a data source. This chapter will be published soon (hopefully!).

Most recently, I have started using my customised Chat GPT 4 as a data analysis tool. I have a project that has a large amount of qualitative data. To help me with a first-level analysis of this large dataset, I have developed a series of 31 prompts based on theories and concepts I know I am likely to use in my research. This has allowed me to start the analysis of my data and give me direction as to areas for further exploration. I have given an example of one of the research prompts below.

In this study, capital is defined as the assets that individuals vie for, acquire, and exchange to gain or maintain power within their fields of practice. This study is particularly interested in six capitals: symbolic capital (prestige, recognition), human capital (technical knowledge and professional skills), social capital (networks or relationships), cultural capital (cultural knowledge and embodied behaviours), identity capital (formation of work identities), and psychological capital (hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism). Using this definition, explain the capitals which have played a part in the doctoral student’s journey described in the transcript.

What I have been particularly impressed by so far is my AIs ability to detect implicit meaning in the transcripts of the interviews I conducted. I expected it to be pretty good at explaining explicit mentions of concepts, but had not anticipated it to be so good at understanding more nuanced and layered meanings. This is a project that is still in progress and I expect very interesting results.

There are some ethical considerations which should be taken into account when using generative AIs.

- Privacy/confidentiality: Data submitted to some generative AIs could be used to train the generative AI further (often depending on whether you have a paid or free version). Make sure to check the privacy statements and always seek informed consent from your research participants.

- Artwork: Generative AIs were trained with artwork without express consent from artists. Additionally, it is worth considering who the actual artist/author/creator of the artwork is when you use generative AI to create it. I consider both the user and the AI as collaborators working to create the artwork together.

- Bias propagation: Since generative AIs are trained based on data from society, there is a risk that they may reflect biases present in the training data, perpetuating stereotypes or discrimination.

- Sustainability: Recent research demonstrates that generative AI does contribute significantly to the user’s carbon footprint.

It is also important to ethically and honestly acknowledge how you have used generative AI in your work by distinguishing what work you have done and what work it has done. I have previously posted a template acknowledgement for students and researchers to use. I have recently updated the acknowledgement I use in my work and have included it below.

I acknowledge that I used a customised version of ChatGPT 4 (OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/) during the preparation of this manuscript to help me refine my phrasing and reduce my word count. The output from ChatGPT 4 was then significantly adapted to reflect my own style and voice, as well as during the peer review process. I take full responsibility for the final content of the manuscript.

My final tip is – be brave! Go and explore what is out there and see what you can achieve! You may be surprised how much it revolutionises your practices, freeing up your brain space to do really cool and creative higher-order thinking!

Questions to ponder

How does the use of generative AI impact traditional roles and responsibilities within academia and research?

Discuss the implications of defining a ‘collaborative’ relationship between humans and generative AI in research and educational contexts. What are the potential benefits and pitfalls?

How might the reliance on generative AI for tasks like grammar checking and data analysis affect the skill development of students and researchers?

The blog post mentions generative AI’s ability to detect implicit meanings in data analysis. Can you think of specific instances or types of research where this capability would be particularly valuable or problematic?

Reflect on the potential environmental impact of using generative AI as noted in the blog. What measures can be taken to mitigate this impact while still benefiting from AI technologies in academic and research practices?

Join my 22 subscribers!